The Storyteller

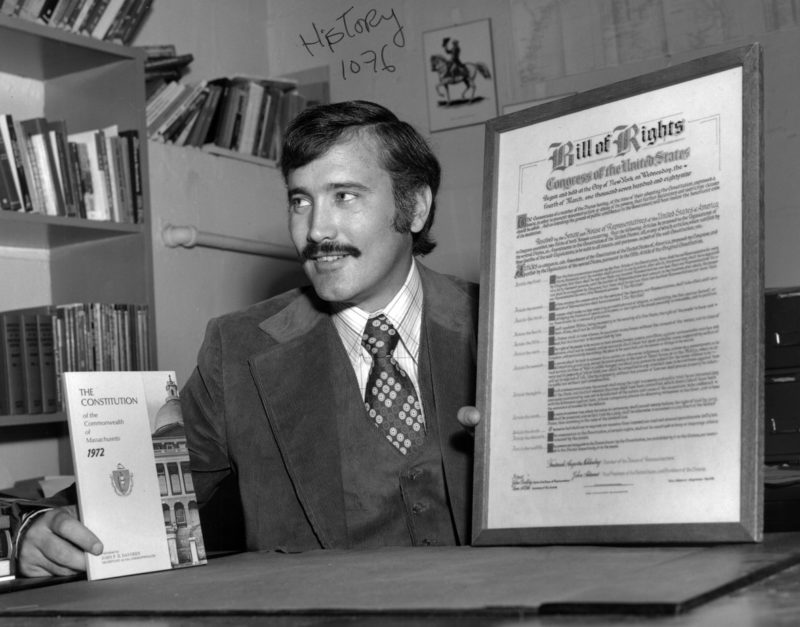

It’s Friday morning, June 30, and Bill Fowler is sitting at his desk in his Meserve Hall office. It’s his final day before retiring. During our hourlong interview, Fowler—wearing not his customary bow tie, but a blue and red checkered collared shirt and khakis—leans forward in his chair and reflects back on more than five decades of association with Northeastern with fondness, pride, and, of course, masterful storytelling chock full of historical facts, sharp wit, and engaging narrative.

Fowler has been part of the Northeastern family for 55 years, beginning as an undergraduate student and then as an alumnus, professor of history, and administrator. In a few hours, he’ll become professor emeritus.

“This is a great university,” he says of Northeastern in 2017. “There is no question about that. When I arrived here in 1962, it was also a great university. I came here as a freshman and I received a wonderful education from a dedicated faculty who held me to very high standards, who taught me well, who supported me and mentored me. I owe a great deal to them in my career success.”

Much has changed since his days as a Northeastern student. “We were white bricks and a gravel parking lot,” he says. He points to everything from new buildings and facilities to a much more diverse student body. Yet, throughout these years two things haven’t changed, two “foundation stones” he says were present in 1962 and are present today: strong faculty and teaching, and experiential education. He would now add “global” as the third stone in the foundation. Taking Northeastern to the next level, the global level for experiential education and research, is President Joseph E. Aoun’s “greatest triumph,” he says.

‘It was always a new experience’

For Fowler, LA’67, H’00, teaching and interacting with students—particularly undergraduates—have made the biggest impact on him during his time at Northeastern. “Every time I’ve walked into a classroom, for any class, it was always a new experience,” he says. “There were new questions. There were new students. It was always new, never boring, always exciting, and always challenging.”

He underscores the value of experiential education and regularly tells his students to embrace co-op and go abroad to get out of their comfort zones. Fowler would know; he says his own co-op experiences as a student shaped his career path and provided key life lessons.

In the 1960s, he worked multiple co-ops at the National Archives, both in Washington and Boston. In the nation’s capital, he worked across the Potomac River at a federal records center in Alexandria, Virginia—a warehouse that formerly served as a World War I torpedo plant. Part of his job involved picking up federal documents from Capitol Hill—many of which would ultimately be disposed of—and bringing back and sorting through them. He recalls one particularly memorable moment in 1963 when he was collecting records from Sen. George McGovern’s office, and the South Dakota senator and historian took time to thank him and ask him about his co-op job. “It was a very gracious moment,” Fowler says.

Fowler’s co-op at the National Archives in Boston, in fall 1963, is also etched in his mind. Following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on Nov. 22, 1963, Fowler was tasked with helping with the transfer of Kennedy’s papers and memorabilia from the White House to a federal records warehouse in Waltham, Massachusetts. “That was a moment in which people of my generation remember exactly where they were when it happened,” he says of Kennedy’s death.

His co-ops at the National Archives taught him several important history lessons, notably the importance of saving documents. “History is written from documents. You need evidence, evidence, evidence.” He also realized the vital role of archivists and librarians in preserving documents and providing the public with access to them.

While Fowler came to deeply appreciate the need to preserve documents, co-op also allowed him to discover his calling to pursue a career in which he could use that information to reach a greater audience.

He wanted to teach.

The definition of success

After graduating Northeastern in 1967, he earned a master’s degree and doctorate from the University of Notre Dame. He then returned to Northeastern in 1971, accepting a position as assistant professor of history. He was promoted to associate professor and awarded tenure in 1977, and was made full professor in 1980. Then his career shifted toward the administrative side of academia, as he served as an assistant to the vice president as well as vice provost for undergraduate education. Fowler returned to the classroom and chaired the Department of History from 1993 to 1997.

Fowler left Northeastern in 1998 to serve as director of the Massachusetts Historical Society. He held that post until 2005, when he returned to Northeastern to teach.

His first charge each semester, he says, was to understand his new students and where their interests lie, and then find common ground. “My task is to weave my story as a teacher and historian into their lives,” he explains. “I need to be relevant. That term is sometimes spoken with disdain, but I don’t look at it that way. It’s fundamentally important.”

A scholar of early American and maritime history, Fowler has often taken his students outside the classroom to experience in person the topics they’re discussing—whether it’s walking Boston’s Freedom Trail or visiting the Mystic Seaport museum. (“They got to throw a harpoon, which of course—when do you get the opportunity to throw a harpoon?” he says of the latter, chuckling.) He says there’s nothing more rewarding than when he’s strolling through the city and he hears a former student’s voice, rushing up to him to say hello and recall these moments.

The definition of success for a teacher is to be remembered, Fowler says, and to know that you’ve helped your students understand something that is relevant to their lives today. “History can be physical,” he says. “It can be sensory. There is a smell, a sight, a sound, a tactile thing. The more you engage students in that kind of experience, the more they remember it.”

‘If he were teaching a class on paint drying, I’d still take it’

Fowler’s colleagues rave about his dedication to the university and his students, as well his intellect and unselfishness.

Heather Streets-Salter, chair of the history department, recalls their first meeting when she was being recruited to Northeastern in 2012. “My first impression was that he was one of the reasons I wanted to come to Northeastern,” she says, recalling how Fowler picked her up at her hotel and walked her to campus, pointing out historical facts about the history of Boston and Northeastern all along the way. “I remember his graciousness, his clear knowledge, and his love of the university,” she says. “It really made me think this is a place I want to be.”

Streets-Salter points to Fowler’s care for and commitment to his students, noting that he’s a compelling and engaging lecturer. She even recruited him to deliver an annual lecture to history students at freshman orientation. “He’s an amazing teacher,” she says. “I always told him that if he were teaching a class on paint drying, I’d still take it. He makes any topic interesting.”

Fowler’s contributions outside the classroom are equally as notable. In 1994 he was presented with the Outstanding Alumni Award in recognition of his service. In 2000, he received an honorary doctor of humane letters and delivered the address to graduates at commencement.

The 2000 commencement program noted that among his many contributions to Northeastern were his efforts in two watershed events. One was that he played an instrumental role in the development of Snell Library. He served on the University Library Building Committee and directed a fundraising campaign for the library that netted $1.5 million. The other was that, in the 1990s, Fowler co-directed the planning for Northeastern’s centennial, a yearlong celebration that explored the university’s history and evolution through an array of historical, educational, and cultural programs, events, and publications.

Fowler has also accompanied students on two Alternative Spring Break trips to Selma, Alabama, one coming in 2015—50 years after the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery. He says he was deeply moved and grateful to accompany the students on that trip and share that experience with them.

Jeffrey Born, professor of finance, has worked for many years with Fowler as part of the university’s cadre of marshals that organizes and serves at commencement and other university-wide celebrations and events. Born, who is now chief marshal, called him a wonderful colleague and great fun to work with, noting his dry sense of humor and the back and forth banter he’d engage in with other marshals before and after these ceremonies.

“He’s a consummate gentleman and scholar, and a wonderful ambassador for Northeastern,” Born says.

‘I was holding one of America’s most important documents’

As a historian, what are the pieces of history he’s physically encountered that have left him awestruck? Two places and a document, Fowler says.

One is the beaches of Normandy, France, where the Allies launched an invasion in World War II, and the American cemetery there. Fowler is noticeably moved as he describes and pauses for a moment before continuing.

The other is Gettysburg. He recalls standing on Cemetery Ridge and thinking about Little Round Top, where during the Civil War the Union’s 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment repelled the Confederate advance on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. “The 20th Maine, just like Normandy, changed history,” he says.

Now, to the document. Fowler recalled that as director of the Massachusetts Historical Society, he “had the keys to everything and I could wander the building.” One day, he was in the vault and pulled down a large leather-bound book of documents. The label read, “Washington’s Newburgh Address.” George Washington delivered that address to American officers at noon on March 15, 1783. Continental army officers’ grievances were mounting and they were on the verge of mutiny, but Washington delivered this eloquent speech that allayed the officers’ fears. The mutiny was avoided. “I was holding one of America’s most important documents,” he recalls. “This was the speech that saved the American republic.”

That moment inspired him to later write a book about the Newburgh Address. “You cannot get any closer to history or an event in history than to hold that document,” he says. “I can’t talk to Washington. I can’t touch Washington. But there I was holding the document that he had written, that he had held. It was his handwriting. It was as close to that event as anyone will ever get. That was a critical moment for me.”

Fowler has written a number of books throughout his career on the American Revolution and on maritime history. His next book, due out in August, is titled Steam Titans, the story of the epic competition between shipping magnates Samuel Cunard and Edward Collins for mid-19th century control of the Atlantic.

“Writing is very important to me,” he says. “You go to the gym to keep your body in good shape; I go to writing to keep my mind in good shape.” He says producing new work, regardless of your discipline, is critical to being an effective university professor. As he puts it, “it’s necessary for your intellectual well-being but also necessary for your students.”

The next chapter

Fowler says his close association with Northeastern will continue in retirement. “After all, I have free parking,” he quips. He’s already thinking about the subject for his next book, and his love for travel will certainly take him on many new adventures.

For more than 30 years Fowler has also taught history aboard sailing vessels, in recent years on larger ships giving lectures on transatlantic voyages of six to eight-weeks. He will continue to set sail on those journeys, lecturing about the places they’re traveling and maritime history as a whole.

“The classroom at sea—it invigorates me,” he says. “Every time I lecture, people come up to me and want to tell me their or their parents’ or grandparents’ stories. I’m enriched by that. It’s a wonderful exchange.”